20 June 2018

Classical music is still a man’s world. Female performers in the entertainment industry learn this early. As a soprano, my career has been defined by playing muses – roles such as Cleopatra (in Handel’s Giulio Cesare), Susanna (in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro) and Rosina (in Rossini’s The Barber of Seville) that were clearly adored by the male composers who created them. Performing them came naturally – after all this is what I had been trained to do. But where was my voice, where was the female perspective? The answer was simple, by and large there’s isn’t one. Almost every portrayal of a woman in the entire regularly performed opera repertoire is constructed through male eyes. The dominance of male composers is, today especially, staggering.

Last week’s Donne – Women in Music report expressed this in stark statistics. Across Europe, 97.6% of classical and contemporary classical music performed in the last three seasons was written by men, leaving a paltry 2.3% written by women.

But why? Is the patriarchy of the music business, the crushing influence of their husbands, or society at large to blame for such a skewed situation?

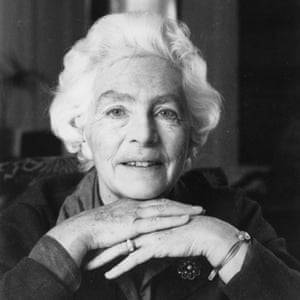

One of our most recent and most strikingly innovative British composers was Elizabeth Maconchy. She was a unique voice, a great talent, and an audible influence on her near-contemporary Benjamin Britten. She was told that as a student at the Royal College of Music she had been passed over for a valuable scholarship because she would “only get married and never write another note!”

She did get married, and had two children, but continued to compose. When she was 23, her work The Land was premiered at the Proms (prompting Gustav Holst to tell her husband: “Keep her at it!”), but it took her nearly a decade to find a publisher, and performances of her music were few and far between. Undeterred, Maconchy continued composing; her favourite form was the string quartet, of which she wrote 13. In 1942, a Royal Albert Hall concert featured her work alongside that of Mendelssohn, Brahms, Dvorak and Tchaikovsky, and in 1952 she won a competition to compose the Coronation Overture. The piece, Proud Thames, was premiered at the Royal Festival Hall in London to critical acclaim. She was the first woman to chair the Composers’ Guild of Great Britain, and she carried on composing until she was nearly 80. And yet her work is almost never heard today and she is little known. Why?

When Robert Schumann married Clara Josephine Wieck, one of the most talented musicians of her generation, what did he give her as a wedding present? You guessed: a cookbook. As if this weren’t enough of a message he also composed Frauenliebe und Leben for her: a song cycle with a clear subtext, a manifesto for dutiful marriage wrapped in romanticism. Clara concluded later:

I once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose – there has never yet been one able to do it. Should I expect to be the one?”

She knew it was possible, that she had the talent: she had, after all, been famous in her own right by the age of 16. Yet she became utterly eclipsed her penniless, unknown husband, Robert. Knowing that the necessary systems of support and education, along with opportunity, platforms and the possibility of critical review were not there for her she instead performed her husband’s works on stage endlessly, and dedicated her life, even after his had ended in madness and premature death, to his elevation.

‘I have been led away from myself’ …

Gustav Mahler made it a condition of marriage to his young bride, Alma, that she give up composing. “I have been firmly taken by the arm and led away from myself,” she wrote.

But this is not just a story about the husbands or patriarchal decision-makers in music. Society at large also stifled women; being a female composer or performer was seen as a highly questionable profession – often implying, in earlier centuries, sexual availability. As a woman, your options were limited, so marriage was a critical economic decision for most, and disregarded at peril. One of the very few alternatives was to take holy orders, a direction which, through chance, the 12th-century writer and mystic Hildegard von Bingen took. Through this vocation, she found a support system and platform for her. Even so, moves were made to mute her. At one point, Hildegard rebuked an archbishop, and as punishment was forbidden to sing.

The mechanisms of the classical music industry have long been a patriarchy. Music is a living thing, and any composer lives via the oxygen of performance, on stage, over the airwaves, and through publishing. Did all those concert promoters, opera directors, orchestra managers and radio controllers simply forget to provide platforms for women? Without a platform, music as a living art form dies.

At one point, my research for the BBC documentary Unsung Heroines led to an all-female student quartet who had named themselves the Maconchy Quartet and were dedicating themselves to performing the composer’s music. It is in these acts, and many others like them, that we can start to turn the tide: to rediscover the lost talents, uncover the forgotten music and give a compelling and inspiring voice to the composers stifled in life or neglected in death. We must celebrate these artists as the collaborative, innovative, unorthodox, irreverent, passionate, daring and resilient people they were.

• Unsung Heroines: Danielle de Niese on the Lost World of Female Composers is on BBC Four on 22 June, 8pm, and then on iPlayer for 30 days.

Leave a Reply