By Marc Bridle

17 Jun 2018

When I reviewed Covent Garden’s Tosca back in January, I came very close to suggesting that we might be entering a period of crisis in casting the great Puccini operas. Fast forward six months, and what a world of difference!

Fast forward six months, and what a world of difference! Vocally, this La bohème is a triumph, musically it’s conducted and played with incredible attention to detail, dramatically it’s the right side of Bohemian.

In an age of austerity, this opera, more than most, is oddly relevant to wider social issues, though a more Marxist-inclined director than Richard Jones – perhaps Calixto Bieito – would probably make those distinctions even more unpalatable. Jones doesn’t delve much deeper than the narrative allows, so interior and exterior lives are as far as it is permitted to go: a barren, threadbare garret, with filthy linen full of holes, a single stove kept alive by the embers of discarded poetry, graffiti painted beams and unaffordable medicines versus the opulence of the Café Momus, with its crystal glassware, plush furnishings, and unaffordable bills. Only the Zeffirelli-inspired touches of romantic snowfall, blazing lights, stuccoed ceilings and palaces of expensive shopping malls give a nod towards a world that sits in uneasy alliance with the commonwealth of economic hardship.

The poverty, and the hand-to-mouth existence, of Bohemianism is quite skilfully captured in this production – at least on the surface. The artist’s paint-spattered trousers, reams of unfinished manuscripts, fossilised bread and copious amounts of opened wine bottles are symptomatic of Paris in the 1840s as they were of London in the 1980s; Café Momus could mirror the Colony Room. The ghosts of Rimbaud and Verlaine are like spiritual forefathers hovering over this staging. One senses that Richard Jones’s Bohemianism is a lived experience. But just as we are voyeurs on the pitiful poverty of Rodolfo, Marcello and Mimì so they are voyeurs on the café society they can’t afford. The choices they make are fraught with narrowness, of the moment and without complexity. Perhaps Jones doesn’t do enough to reveal how depraved an opera La bohème really is; it seems to me this is less a tragic love story, and much more an opera about perverted priorities. Given a choice between paying Benoît his rent arrears or plying him with drink and flattery to trick him into indiscretion, the latter is chosen and a night on the Quartier Latin follows. When the moral compass of Rodolfo, Marcello and Musetta is finally engaged towards the true extent of Mimì’s fate it is beyond redemption. Bohemianism is a life without responsibility.

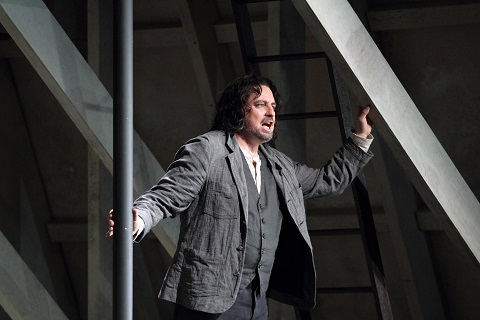

Matthew Polezani as Rodolfo. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

There is, I think, a yawning gap between the romance of Rodolfo and Mimì and the “bromance” of the boys in this production. Rodolfo and Marcello, in particular, had the kind of metrosexual relationship that one felt was constantly pushing boundaries. The symmetry of them both climbing the rafters in the garret and pumping their groins against it had the ritual, and ballet, of insects mating. In contrast, Rodolfo and Mimì often felt awkward together – and relied exclusively on their singing to push their romance. I’m not sure it helped one bit that Mimì looked exceptionally dour – I think if I had been Rodolfo I wouldn’t have bothered to light her candle, and I’d have thrown away her lost key. She looked positively Dickensian. Marcello and Musetta, however, were almost flagrant in their sexuality during her drunken waltz scene in Act II but by Act III this relationship has come to an explosive end as Marcello throws Musetta and her belongings out of the Tavern into the snow. If the one relationship is awkward this one is anything but: it’s passionate, intense and inflames the stage with emotion. It was almost unbearable to watch.

But Danielle de Niese, as Musetta, is nearly in danger of overwhelming this production. She is magnificent. Her voice is an incredibly powerful instrument, riding over the orchestra with shattering high notes. Her “Quando m’en vo” was unforgettable, sensual, flirtatious and beautifully even of tone. Riveting to watch, she brings complexity to the character of Musetta: in Act II she exudes all the humour of a table-top dancer, in Act III you begin to feel this is a woman with depth of emotion as she trudges through the snow, and by Act IV her pathos has come full circle as she thinks only of selling her ear-rings to rescue Mimì from impending death. Musetta is clearly on a journey in this production – and Richard Jones and the costume designer, Stewart Laing, spare no effort in pointing this out quite explicitly: her dresses change throughout the production from fiery red, to a purified yellow, and finally a neutral dark.

Danielle de Niese as Musetta and Maria Agresta as Mimì. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Our Bohemian “boys” experience no such epiphany, but again the singing is first rate. Matthew Polenzani’s Rodolfo might be too light for my tastes – I probably prefer a tenor who is darker, more plaintive and haunting (such as Sandor Konya, or even Domingo). Having said that, the lyricism of this tenor was unquestionably superb on opening night – and he was nowhere better than in “Che gelida manina” which, although being so cruelly exposed for the tenor, was brought off with considerable beauty and breath-taking poise (no need to transpose the high C down here). As I’ve hinted at earlier in this review, the Rodolfo and Mimì in this production conveyed much of their passion through their singing rather than the chemistry of their acting – which is somewhat against convention since by no stretch of the imagination could the role of Rodolfo really be considered a dramatic tenor part. That Polenzani manages to do that is a formidable achievement. If, ultimately, he lacks the hybrid of honeyed and Italianate warmth (this is a particularly Anglo-Saxon sung performance at times) he’s nevertheless entirely credible as both a lover and a Bohemian poet; the voice is entirely focussed at full stretch and his diction is clear. It was also a plus to hear a singer in this house finally sing some Puccini as the composer wrote it in his score – the soto vocemarkings are there if one bothers to sing them.

Maria Agresta’s Mimì – despite looking a drudge and anaemic for much of the opera, but I guess that comes with this most unglamorous of roles – achieves something quite rare in the part: she makes Mimì sound like Mimì and not like any other Puccini tragi-heroine. Every word had meaning, an expressive range that extended from her emotions of love through to despair. If de Niese’s Musetta had been an instrument of power, almost like steel in its ability to soar over an orchestra, Agresta’s voice is darker, richer – more like an iron fist wrapped in a velvet glove. The voices are entirely complementary. If Agresta’s Mimì isn’t the most moving I’ve heard, it’s entirely involving with enough vocal colour to avoid giving the impression that Mimì has been dying since Act I (some singers, believe it or not, sometimes make you feel this is the longest death scene in opera).

Duncan Rock as Schaunard, Fernando Radó as Colline, Etienne Dupuis and Matthew Polezani as Rodolfo. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The rest of the cast is also very strong. Etienne Dupuis, as Marcello, has a beautifully defined baritone voice; I found him entirely compelling to watch and listen to, as I also did Duncan Rock as Schaunard. Both Dupuis and Rock have different kinds of baritone voices (a notable feature of this production is the very careful vocal casting of the major roles): Rock’s is darker, Dupuis’s slightly higher in range, often making me wonder whether the role of Rodolfo might one day be within his grasp (even if he does have to transpose down to a B flat some of those high notes). Fernando Radó was an exemplary Colline.

After the orchestra’s lacklustre playing back in January I had almost despaired hearing them play Puccini again. However, under the Italian Nicola Luisotti they were often inspired. Perhaps being sat in the fifth row from the stage, to the right of the orchestra pit, I was perhaps prone to a slightly more brass-heavy sound than usual – but the playing was transparent (the harp, for example, was entirely clear to me) and I can’t recall this orchestra playing Puccini with such lush, beautifully passionate playing. Luisotti neither lingered over the score, nor lost a grip on the drama and he supported his singers beautifully.

I’ve often come away from a performance of La bohème recalling Benjamin Britten’s thoughts on the opera: “After four or five performances I never wanted to hear La bohème again. In spite of its neatness, I became sickened by the cheapness and emptiness of the music.” The Royal Opera’s La bohème, especially when it’s this superbly well cast and played, does make me rather want to stick with the work.

Performances through to 20th July 2018, with cast changes.

Marc Bridle

Puccini: La bohème

Mimì – Maria Agresta, Rodolfo – Matthew Polenzani, Marcello – Etienne Dupuis, Musetta – Danielle de Niese, Schaunard – Duncan Rock, Colline – Fernando Radó, Benoît – Jeremy White; Director – Richard Jones, Conductor – Nicola Luisotti, Sets and Costume – Stewart Laing, Lighting – Mimì Jordan Sherin, Movement – Sarah Fahie, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; 16th June 2018.

Leave a Reply