February 17, 2026

by Fiona Maclean

English National Opera at the London Coliseum Presents Brecht and Weill’s City of Mahagonny in a New Production

In the hedonistic city of Mahagonny, almost everything is allowed. Eating, sex, fighting and getting drunk are celebrated. But everything has its price. A designer town, built from scratch by three criminals on the run from justice, seems like an implausible starting point, yet the city grows quickly as people flock to enjoy a lifestyle with no boundaries. Director Jamie Manton’s Mahagonny is a contemporised city, somewhere towards the Gulf of Mexico, something like an American boom city of the 1920s, but one built on hot air rather than commerce, manufacturing or construction. What could possibly happen to burst that bubble?

The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny was written at a crucial moment in the collaboration between Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht, growing out of the success of their 1927 Mahagonny Songspiel, a sequence of songs with instrumental links that they decided to expand into a full-scale opera. The piece is often seen as a transition for both artists: for Brecht, as his thinking moved more decisively towards Marxism, to the extent that he even published a more overtly political third version of the libretto, a step that helped drive a wedge between him and Weill; and for Weill, as he experimented across a spectrum from grand opera to music theatre. In the opera, the sharper, cabaret-like songs of the Songspiel are absorbed into a more serious musical texture, and the work was originally conceived and premiered with trained opera singers, just as performed by ENO rather than as Music Theatre.

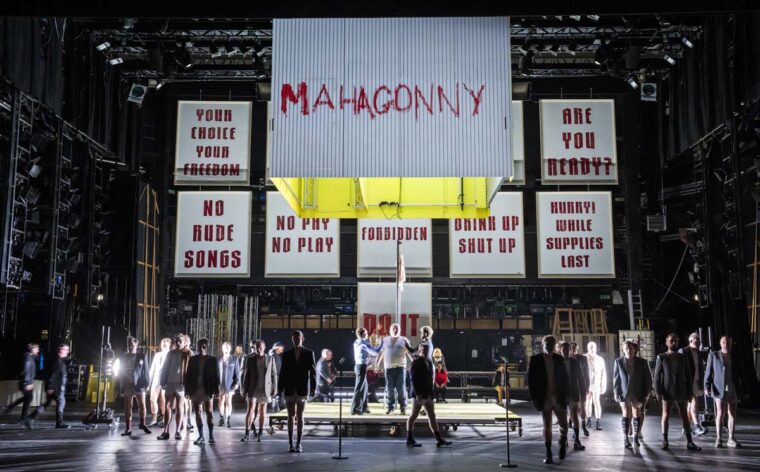

Somehow, this satirical production that challenges capitalism seems strikingly relevant at a time when cultural values are being eroded, and money can apparently buy anything. Designed by Milla Clarke, the sets are visually stark. The criminals (Rosie Aldridge as Leokadja Begbick, Kenneth Kellogg as Trinity Moses and Mark Le Brocq as Fatty the Bookkeeper) arrive to set up base in a lorry trailer, which is transformed into various rooms throughout the opera. Jenny arrives in town with her girls (and boys), walking ‘forward’ on a treadmill, a device that is used on several occasions. The chorus appears from the stalls and circle boxes, taking selfies while they sing. They are the bourgeoisie who flock to the city of Mahagonny, attracted by a self-indulgent life. Four friends (Simon O’Neill as Jimmy MacIntyre, Alex Otterburn as Bank-Account Billy, Elgan Llyr Thomas as Jack O’Brien, and David Shipley as Alaska Wolf Joe) arrive from Alaska, having worked for seven years to save the money to come to this decadopolis.

The vast auditorium of the London Coliseum, with gilded moulding framing velvet seats, made a marked contrast to the bleak, dark stage, where the chorus was simply dressed in grey suits or in stark whiteunderwear. Lead roles were given a more flamboyant treatment, with Jenny (Danielle de Niese, in her element) in the kind of clothes that would have made Vivian Ward in her ‘former’ life happy, and with Rosie Aldridge appearing in a sage-green boiler suit topped with a mop of Titian locks.

Of course, we all know and love the Alabama Song. There are very few operas that can claim a number that has been covered by The Doors and David Bowie, among others. De Niese produced a fine opening rendition, although her supporting ‘girls’ took some time to get into their stride. Snippets of the song appear throughout the opera, a poignant reminder of the ethos of Mahagonny. Rosie Aldridge as Begbick was equally vocally powerful and a thoroughly convincing leader of the fleeing criminals, with her transformation into ‘judge’ in Act III offering a chilling insight. Simon O’Neill as Jimmy MacIntyre was, for me, the standout performance, with a mellifluous tenor perfectly matched by his stage presence and acting skills.

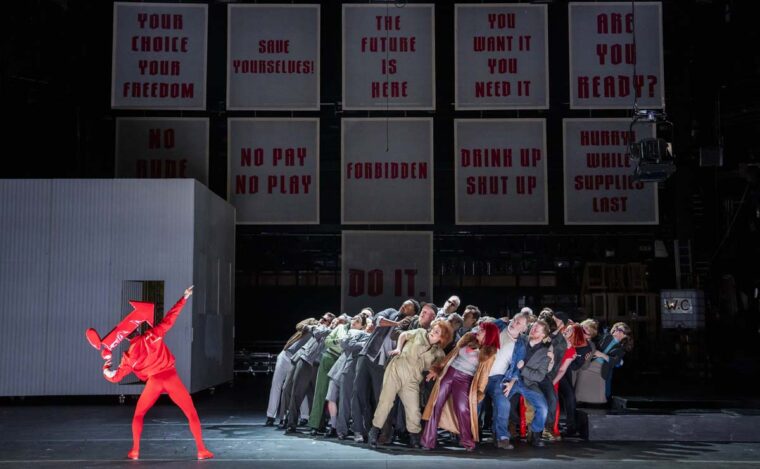

The powerful leads were supported by an exceptional chorus. Acting and dancing impeccably, with all singing perfectly in sync, they formed the foundation of the production. There were countless brilliant moments throughout The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Elgan Llŷr Thomas’s moment in First, Don’t Forget Eating, where he claims to have eaten a calf and ten baby calves before dying of overindulgence, was gruesomely memorable. I was also particularly taken with the tap-dancing Typhoon (Adam Taylor), who somehow manages to go in the wrong direction despite wearing a large red arrow. And, the onstage piano playing from Murray Hipkin was stunningly virtuosic.

The orchestra, under the baton of ENO’s new Musical Director, André de Ridder, was impeccable. This kind of music requires a particular skill set from players who are generally more accustomed to Mozart and Beethoven. The score ranges from a cappella chorales for the singers to jazz, popular dance music, cabaret and music hall numbers, alongside more symphonic, through-composed passages that show Weill’s training and his link to the classical tradition. Pulling all of this together into a cohesive whole is no mean feat. The only issue was the lack of smoothness between some amplified sections, mostly spoken-word passages, and the operatic singing. In the vast space of the London Coliseum, there was probably little choice, but for me, the result was the occasional aural hiccup.

As an evening of pure entertainment, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny offers a bridge between classic opera and musical theatre. But, more than that, there’s a clear political point to the work. Near the end of the opera, Jimmy is executed not for murder or violence but because he can’t pay his debt (in fact, a murderer is pardoned in the preceding trial, thanks to a large bribe). The opera isn’t just being moralistic about decadence; it’s arguing that a society ruled by market forces and consumption alone is inhumane and destructive. Even the ‘god’ who appears at the end (and talks about taking everyone to hell) is there to expose the futility of hoping for transcendence in a world ruled by capitalism.

Whether you choose to see Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny for the pure entertainment value or for the underlying satire and bitter messages, it’s an excellent production. With just two remaining performances, it’s one not to miss.

16 – 20 February 2026

Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny

English National Opera

London Coliseum

St Martin’s Lane

London

WC2N 4ES