Written By Sebastián Spreng

October 25, 2024 at 12:53 PM

Kudos to the New World Symphony (NWS) and its artistic director Stéphane Denève for staging two unusual brief operas in one evening, a milestone counts as double if that undertaking takes place in Miami, where the operatic outlook grows more sparse and discouraging by the year.

Another reason for a seal of approval is that the season has been programmed to commemorate the eightieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

It’s a challenge to stage works for audiences, who are sometimes uncomfortable if not reluctant to unfamiliar pieces. Still, the reaction here was either absorbed or puzzled by this memorable weekend offering at New World Center in Miami Beach.

Originated during the fateful years between 1933 and 1943,

along with Kurt Weill’s “The Seven Deadly Sins” constitute artistic and political statements of a horrific era by composers who would die too young (46 and 50 respectively) in very different circumstances. Weill had a heart attack during his American exile, and Ullmann died exterminated in Auschwitz. Coincidently, this weekend’s performance marked the anniversary of Ullman’s death in the gas chamber.

[RELATED: Read the preview story: New World Symphony’s Bold Opera Double Bill]

Vital allegorical pieces assembled in a risky but ingenious “ying-yang” program concocted by Denève, both are epic operas at the service of the text rooted in the tradition of the “German Singspiel” with pivotal elements of the Berlin cabaret, jazz, and klezmer, then labeled as “Degenerate Art,” and musical complement to the sarcastic Otto Dix and George Grosz paintings.

Both are irrefutable samples of cultural resilience to barbarism and another poignant case of art blooming in complete chaos. Ullmann composed his opera (and an enormous body of work) interned in Terezin, the sinister “model concentration camp” that served as an infamous smokescreen for the regime. In the meantime, as a Paris refugee, Weill was about to emigrate to the United States with his muse, Lotte Lenya.

While he had Bertolt Brecht’s vitriolic texts, delighted to sink his teeth into “The Seven Deadly Sins,” Ullmann had as librettist the young Peter Kien, painter, poet, and writer extraordinary creating a story of astonishing audacity. It is hard to imagine staging this mockery of Emperor “Overall” who declares universal war (note that same year Goebbels declared “Total Krieg”).

At the same time, death abdicates its task offended by the imperial decree only to return if the emperor is his first victim. Needless to say, when the Nazis realized “who the emperor was,” canceled the premiere and hastened the deportation of both to Auschwitz. Luckily, a librarian saved the score, and the opera premiered as late as 1975.

Clever and compelling, small orchestrated for obvious reasons, “Emperor” shows Ullmann’s distinctive language also carrying a myriad of hidden but recognizable musical quotes, from Hindemith and his teachers Schönberg and Zemlinsky to Mahler’s “Song of the Earth,” Weill’s “Song of the futility of human struggling,” Berg’s “Wozzeck,” the nymphs of the Straussian “Ariadne,” the witch of “Rusalka,” a traditional lullaby and even the distorted German anthem and a Bach choral all exquisitely intertwined.

In the antipodes, “The Seven Sins” is a walk through the American vastness.

But tread carefully.

One can come out of the embers to fall into the fire when Brecht exposes the risks and misadventures of the American Dream. He paints the seven-year journey by sisters Anna I and II (one in two, one the practical, the other the emotional) through seven cities, facing seven sins to buy a little house in Louisiana. The fascination with the American culture reflected by Weill just with a nostalgic clarinet or the family quartet that, like a ferocious Greek choir, comments, reproaches, and demands to the sisters, are only sides of this curiously hybrid opera-ballet created for Lenya and dancer Tilly Losch, produced and directed by George Balanchine in Paris in 1933.

From the original Lenya and the definitive Gisela May to Milva and the more academic von Otter and Stratas in Peter Sellers’ film, each singer provides invaluable approaches.

Second to none, the NWS featured the versatile Danielle de Niese, who played both singer and dancer, the two Annas, in a deliberately kitsch staging by Bill Barclay. De Niese excelled, mastering every vocal and scenic challenge. The family was convincingly embodied by Balke Denson, Ricardo García, Lucia Lucas, and Logan Wagner.

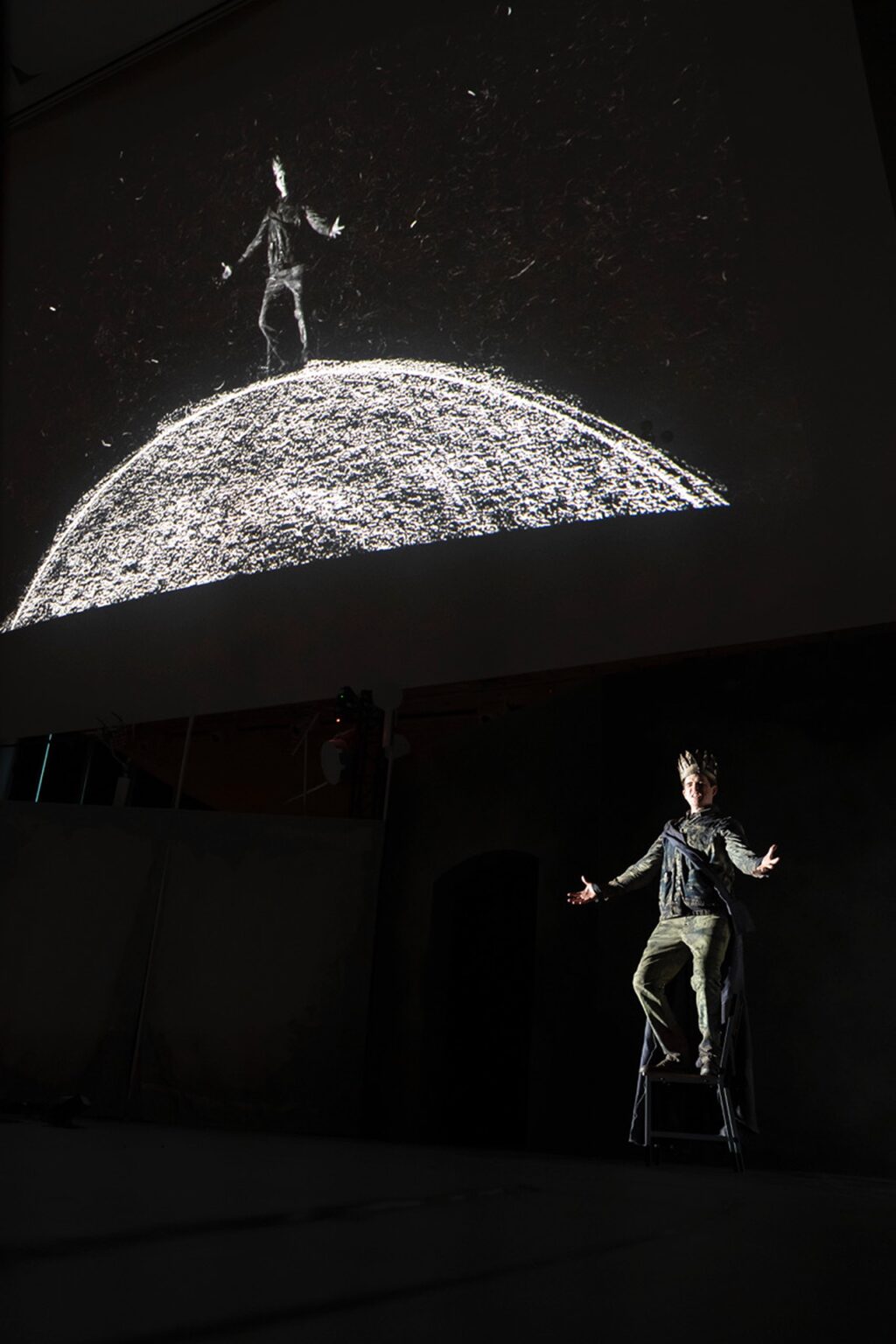

At the NWS, “The Seven Deadly Sins” and “The Emperor” received exemplary renditions thanks to a first-class creative team. Curiously, Ullmann’s opera was even more “Brechtian ” than Weill-Brecht’s due to Yuval Sharon’s perfect alignment with Brecht’s principles and aesthetics: Theater to think and reflect instead of pure entertainment, creating enough distance not to get too emotionally involved; and, in the end, a representation of reality and not reality.

Under his direction —along with Alexander Gedeon — the intelligent use of puppets, projections, and drawings in an ascetic and effective way highlighted the message and where it originated.

Honors to the impressive vocal team: Emmett O’Hanlon, Chauncy Packer, and Freddie Ballentine are three names to remember. It is worth mentioning that Sibyl Wickersheimer, Yuri Okohana-Benson, Yuki Link, and Wilberth Gonzalez are responsible for this timeless setting where the creepy past arises, predicting an even more disturbing future. In the end, in Chinese shadows, the cast returns to their bunks in their barracks, from where they left to start representing this masquerade.

It would be unfair not to highlight the contribution of Denève and the NWS fellows, who took advantage of training in a different and demanding genre and enjoyed the challenge they solved splendidly in each accent, phrase, and variation.

Years ago, NWS marked a milestone with Bartok’s “Bluebeard Castle.” Today, this double bill belongs to the same revealing league of welcomed and essential works, pieces committed to their time but, unfortunately, more valid today than ever.

The next NWS concert, on Saturday Oct. 26, at the Arsht Center, will feature “The Planets” by Holst, the prelude of “Tristan and Isolde” and the “Variations on a Rachmaninoff theme” with Alexander Malofeev conducted by Molly Turner and Xian Zhang.

Leave a Reply